NELP | RETALIATION FUNDS: A NEW TOOL TO TACKLE WAGE THEFT | APRIL 2021

0

REPORT| NOVEMBER 2022

How California can

Lead on Retaliation

Reforms to Dismantle

Workplace Inequality

Authors:

Tsedeye Gebreselassie

Nayantara Mehta

Irene Tung

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

1

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ruth Silver Taube (Santa Clara County Wage Theft Coalition), Tia

Koonse (UCLA Labor Center), Christopher Calhoun and Azucena Garcia-Ferro (SEIU California),

and the membership and leadership of the California Coalition for Worker Power (CCWP) for

their contributions to this report. Photo credits: Fight for $15 and a Union, Trabajadores Unidos.

Special thanks to our former NELP colleague Laura Huizar, for her leadership in developing the

details of a retaliation fund.

We would also like to thank our NELP colleague Paul Sonn, for his contributions to policy

development on just cause protections, and colleagues Cynthia Montes, Mónica Novoa, Eleanor

Cooney, and Norman Eng for their expertise and support in the production of this report.

About NELP

Founded in 1969, the nonprofit National Employment Law Project (NELP) is a leading advocacy

organization with the mission to build a just and inclusive economy where all workers have

expansive rights and thrive in good jobs. Together with local, state, and national partners, NELP

advances its mission through transformative legal and policy solutions, research, capacity building,

and communications. For more information, visit us at www.nelp.org

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

2

Contents

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 4

I. Few Workers Who Experience Workplace Violations Report Them, and the Majority of

Those that Do Report Experience Employer Retaliation as a Result .................................. 8

II. Workers Cite Concerns about Employer Retaliation and the Threat of Job Loss As Major

Reasons for Not Reporting Employer Violations ............................................................. 10

III. Given Widespread Economic Precarity in California, Retaliatory Firings Can Have

Catastrophic Consequences for Workers ......................................................................... 12

IV. California’s Anti-Retaliation Laws Fall Short Because They Force Workers to Bear

Significant Financial Risk Before Holding Employers Accountable ................................... 14

V. Unjust and Arbitrary Firings: California’s At-Will Employment System Creates an

Enormous Power Imbalance Between Workers and Employers, With Far Reaching

Consequences in the Workplace and Beyond .................................................................. 15

A. At-Will Employment Allows Employers to Fire Workers for Almost Any Reason or No

Reason at All 15

B. Unfair and Arbitrary Firings are Common 17

C. At-Will Employment Coerces Workers into Accepting Harmful and Illegal Working

Conditions 18

VI. Policy Recommendations: A Retaliation Hardship Fund, Consistency Across the Labor

Code, and a State “Just Cause” Standard ......................................................................... 19

A. Create a Retaliation Fund to Provide Workers with the Financial Support They Need

When an Employer Retaliates 19

B. Simplify California’s Anti-Retaliation Laws to Help Workers Understand and Assert

Their Rights 20

C. Adopt a State “Just Cause” Law to Protect Workers from Unfair and Arbitrary Firings

21

VII. Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 21

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

3

Appendix A – Key Elements of a Retaliation Fund ........................................................... 22

Appendix B – Key Provisions of a “Just Cause” Law .......................................................... 25

Appendix C – Survey Methodology ................................................................................... 29

Endnotes ........................................................................................................................... 30

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

4

Introduction

“I think of my family. One has to work to survive. In this country and in this state, it is too

expensive. Rent, food, everything is very expensive. But it is true that I have seen so

much injustice, sometimes it even gives me fear, [but] I think, ‘What job am I going to

find?’ because I have seen over the years that in the fast food industry there is a lot of

discrimination, wage theft, many injustices that all workers experience. So that's why I

like to participate, because this fear truly has to end. Being able to raise my voice has

served a lot to my colleagues. They have followed me, been with me, and they have been

able to raise their voices too.”

1

“After our boss knew that we were taking collective action, she was furious and began to

cut our hours, give us the hardest shifts, like the closing shifts, and even fired employees.

Retaliation is so common because many immigrant workers don’t know their rights. We

need to ensure a safe workplace and protection from retaliation, especially during this

pandemic, when restaurant workers have to interact with customers and may be scared

to speak up. I hope that other workers will hear our story and learn and protect their

rights.”

2

Workers across California in sectors such as food service, car wash, and caregiving are

coming together to fight for owed wages and safer working conditions. The quotes

above come from, respectively, the Fight for 15-led campaign for better conditions in

the fast-food industry and a three-year organizing campaign supported by the Chinese

Progressive Association and the Asian Law Caucus, which resulted in 22 restaurant

workers recovering $1.6 million in stolen wages.

These campaigns are powerful examples of worker action and solidarity. However, there

remains a fundamental power imbalance between workers and employers that makes it

difficult for workers to raise complaints and take collective action to improve workplace

conditions. Because employers can fire workers for almost any reason—or for no reason

at all—under California’s system of “at will” employment, workers often experience

retaliation when speaking up about workplace conditions. Widespread economic

insecurity makes the threat of losing one’s job or income as a result of employer

retaliation especially and immediately catastrophic.

To better understand the impact of employer retaliation and at-will firings in California,

the National Employment Law Project (NELP) commissioned YouGov to conduct a survey

of 1,000 adults in the California workforce in January 2022. The survey sample included

workers aged 18-64 across the income spectrum and was representative by age, gender,

race, and years of education. Survey responses revealed a high prevalence of workplace

violations, low rates of violation reporting, high rates of employer retaliation, and

frequent unfair and arbitrary firings. Key findings include:

• Thirty-eight percent of California workers have experienced a workplace

violation.

»

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

5

• Only 10 percent of those workers reported them to a government agency, and

almost half (47 percent) did not report violations to anyone.

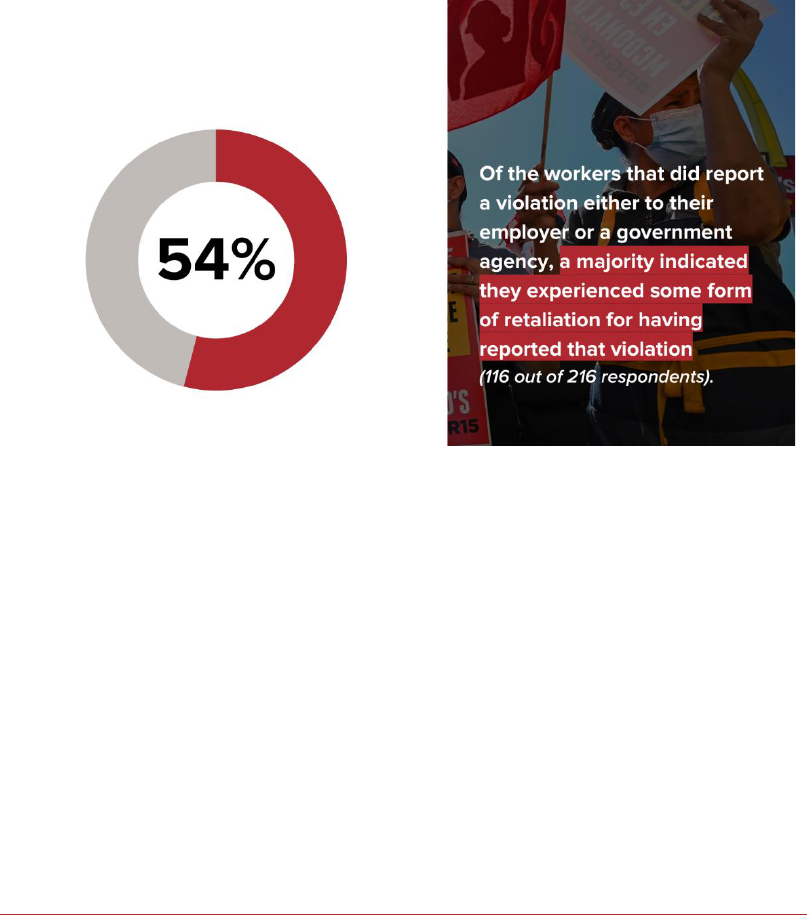

• Of the workers who reported violations to their employer or to a government

agency, a majority (116 of 216 respondents) experienced employer retaliation.

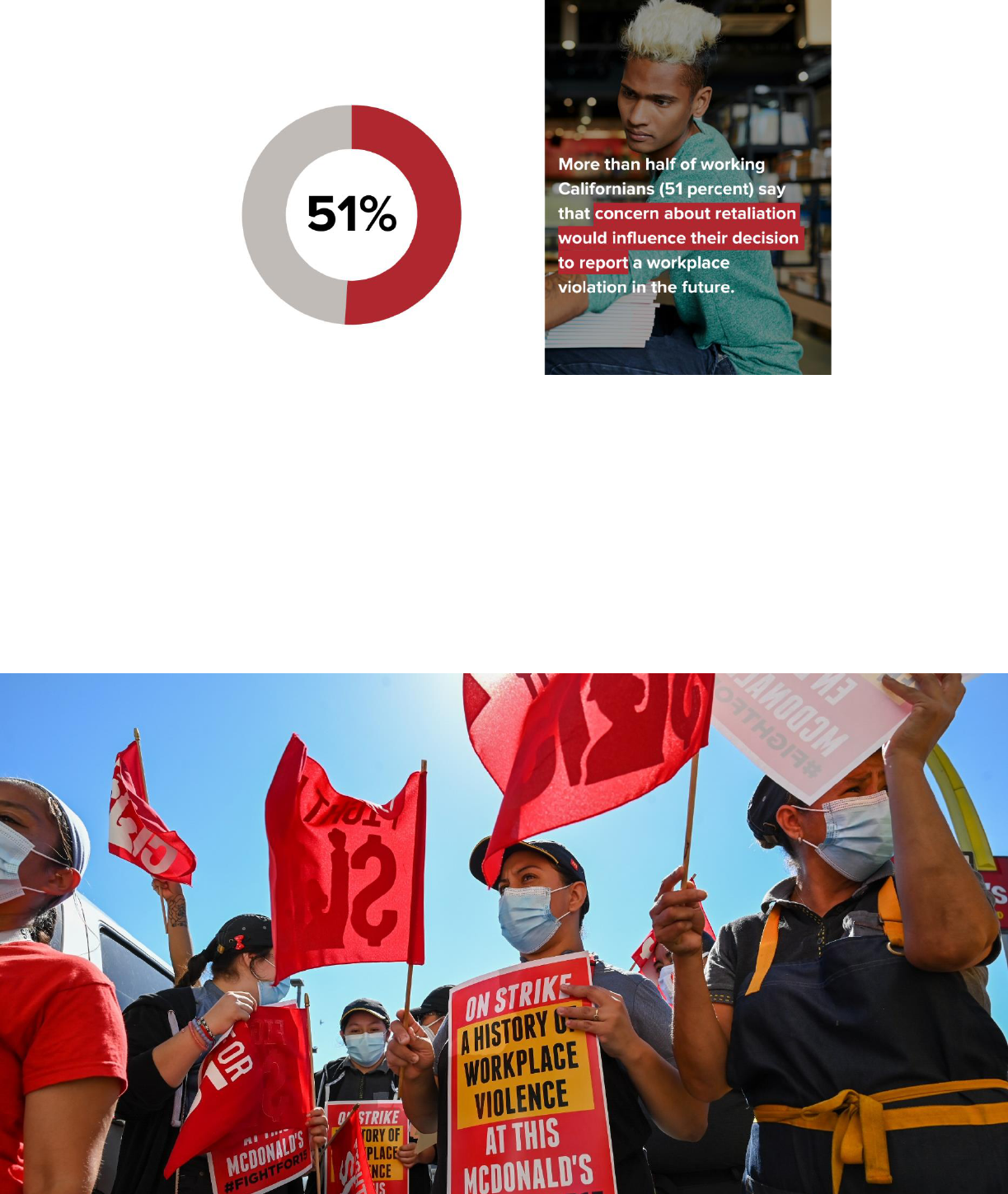

• Fifty-one percent of working Californians said that concern about employer

retaliation would influence their decision about whether or not to report a

workplace violation in the future.

• More than two in three California workers said access to a hardship fund that

would provide them immediate monetary relief if they were retaliated against

could help them report a future violation to a government agency.

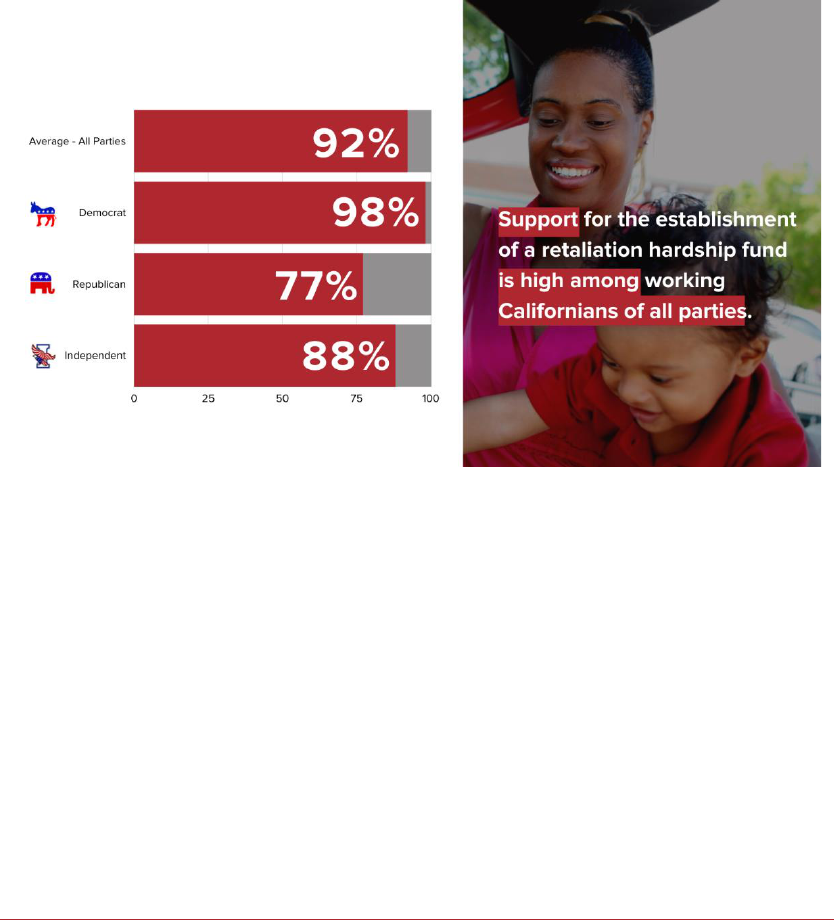

• An overwhelming majority of working Californians—92 percent—support the

establishment of a retaliation hardship fund that would provide one-time

financial assistance to workers who file good faith complaints about employer

retaliation.

• Forty-one percent of California workers have been fired or let go at some point.

Less than one third of those workers (29 percent) said they were given fair

warning before being fired, and most (64 percent) said they have never received

severance pay.

• More than 40 percent of workers—including 46 percent of Latinx workers and

55 percent of Black workers—said that concern about being fired or disciplined

may have prevented them from joining their co-workers to push for job

improvements.

• A large majority of working Californians of all political parties—81 percent—

support the adoption of laws protecting workers from unfair and arbitrary

firings.

This report builds on the survey’s findings to examine how retaliation and unfair firings

permitted under today’s at-will employment framework put workers at a fundamental

disadvantage when it comes to exercising their rights. The report highlights the costs of

this power imbalance for workers and their broader communities and offers the

following policy recommendations to California lawmakers:

• Establish a retaliation fund to provide workers with the immediate economic

support they need to exercise their rights.

• Bring the state’s varied and complex array of anti-retaliation laws into harmony

and ensure that the same protections for workers exist across the California

Labor Code.

• Create a rebuttable presumption of retaliation within 90 days and ensure that

penalties for retaliation consistently go directly to the worker rather than to the

state’s general fund.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

6

• Increase funding for the Labor Commissioner’s Retaliation Complaint

Investigation Unit to support its enforcement of more than 45 labor laws.

• Adopt a “just cause” policy to address arbitrary and unfair firings.

The first two sections of the report detail the survey’s findings that few workers who

experience workplace violations actually report it, and of those that do, a majority

experience employer retaliation as a result. These findings are borne out by complaint

data collected from the state’s main workplace enforcement agencies. This retaliation is

a major reason why workers do not come forward. The third section of the report

describes some of the immediate catastrophic consequences that flow from employer

retaliation, with many workers already just a paycheck or two away from being unable

to cover their bills. Section 4 highlights some of the inadequacies in existing state anti-

retaliation laws that force workers to bear significant financial risk before holding

employers accountable. Section 5 situates workers’ experiences in California’s at-will

employment system, where most employers can legally fire workers with no notice for

almost any reason or no reason at all. At-will employment creates a climate of fear that

undermines workers ability to speak up about mistreatment, and perpetuates

longstanding racial inequities in the workplace. The survey’s data confirms this, finding

that unfair and arbitrary firings are common among California’s workforce and that the

threat of these firings coerces workers into accepting harmful working conditions.

Finally, Section 6 offers the policy recommendations listed above.

Why Do Workers Experience Retaliation?

Numerous studies confirm that workers, especially those in low-paying industries,

experience high rates of workplace violations, including wage and hour violations,

unsafe working conditions, and more. But workers in the US generally bear the burden of

enforcing their own labor protections—worker complaints are virtually the only way that

violations are brought to the attention of public agencies or the courts. When a worker

comes forward to report a workplace violation, we know that employers often retaliate

or threaten to retaliate against the worker. Under our current system, workers bear the

entire risk of retaliation from their employer when they report violations.

What Does Retaliation Look Like?

Retaliation takes many shapes and can be difficult to pinpoint or prove. Employers, for

example, may fire a worker, demote a worker, reduce a worker’s hours, change a

worker’s schedule to a less favorable one, subject a worker to new forms of harassment,

unfairly discipline a worker, threaten to report a worker or a worker’s family member to

immigration authorities, blacklist workers from future employment, and much more.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

7

What Does Retaliation Cost Workers?

When workers experience retaliation for trying to protect their rights, the costs can

quickly escalate from both a financial and emotional standpoint, especially for the

countless workers nationwide who live paycheck to paycheck. A worker may experience

lost pay, for example, which can lead to missed bill payments, lower credit scores,

eviction, repossession of a car or other property, suspension of a license, inability to pay

child support or taxes, attorney’s fees and costs, stress, trauma, and more.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

8

I. Few Workers Who Experience Workplace Violations Report

Them, and the Majority of Those that Do Report Experience

Employer Retaliation as a Result

Our survey of California’s workforce found that 38 percent of respondents have

experienced a workplace violation, but only 10 percent of those respondents reported

the violation to a government agency. While more than a quarter (26 percent) have

reported a violation to human resources and 29 percent have reported a violation to

their supervisor, almost half (47 percent) of workers who experienced violations did not

report them to anyone.

Of the workers who did report a violation, either to their employer or to a government

agency (216 respondents), a majority (116 out of 216 respondents) indicated they

experienced some form of retaliation for having reported that violation.

State agency data, detailed below, corroborate our findings that employer retaliation is

a serious problem in California with California enforcement agencies receiving tens of

thousands of complaints each year alleging unlawful retaliation. Three of the principal

agencies tasked with handling retaliation complaints for California workers are the US

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the Retaliation Complaint

Investigation Unit (RCI) within the California Labor Commissioner’s Office, and the

California Civil Rights Department (formerly the Department of Fair Employment and

Housing) (CRD). The EEOC handles complaints concerning workplace discrimination and

related retaliation under various federal laws,

3

RCI enforces over four dozen California

retaliation protection statutes,

4

and the CRD enforces the Fair Employment and Housing

Act, Unruh Civil Rights Act, Disabled Persons Act, Ralph Civil Rights Act, Trafficking

Victims Protection Act, and other anti-discrimination laws involving state-funded

activities, along with retaliation stemming from workers’ reliance on those laws.

5

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

9

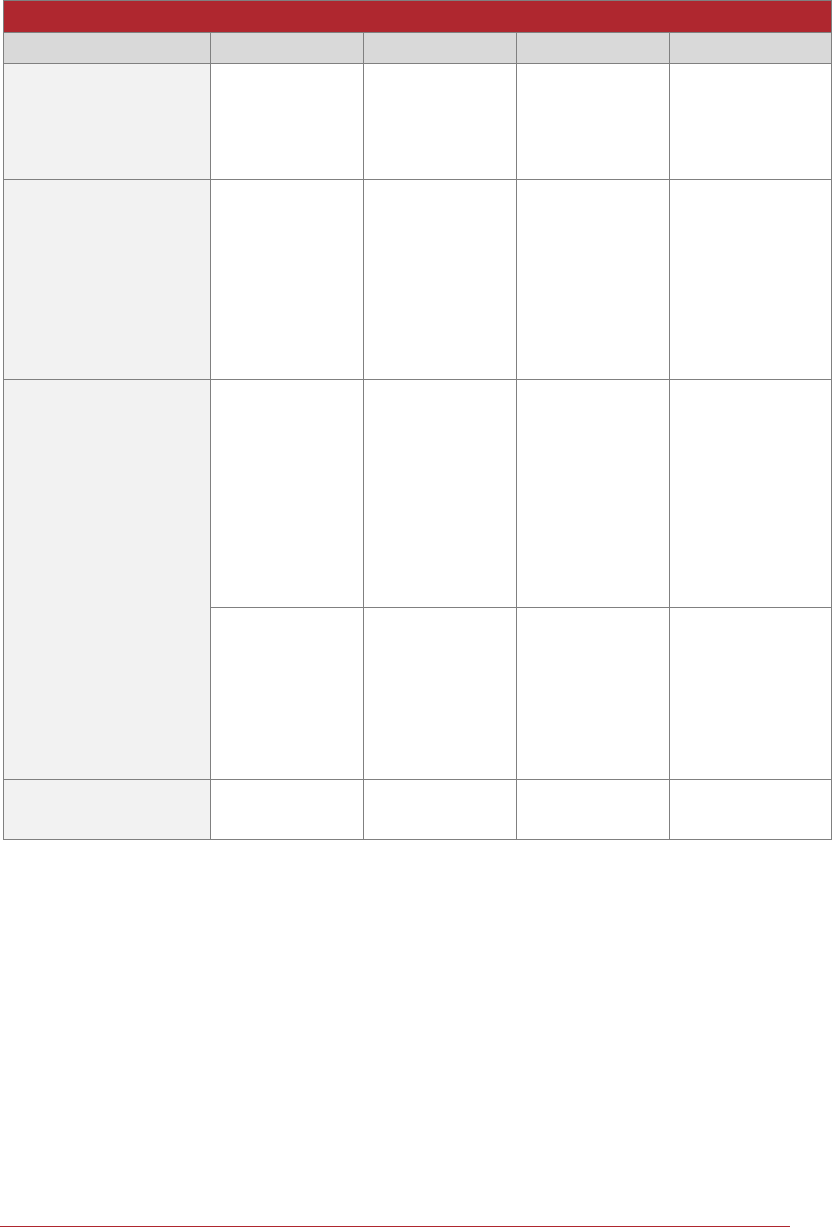

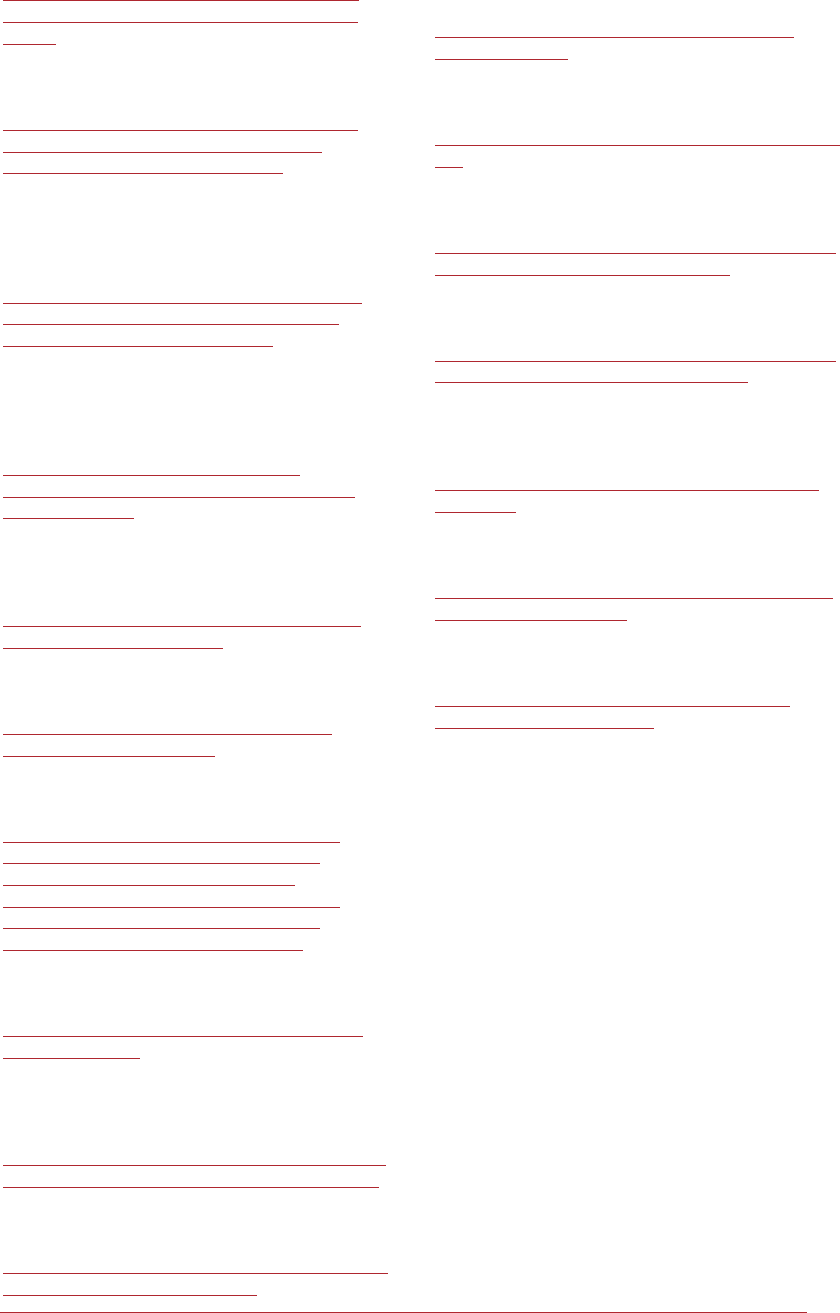

Data from these agencies spanning 2017 through 2019 shows:

• California workers submitted more than 69,000 complaints alleging retaliation to

the EEOC, RCI, and CRD.

• In 2019 alone, the EEOC, RCI, and CRD received more than 24,000 complaints

from California workers alleging unlawful retaliation.

• At the EEOC and CRD, retaliation complaints made up a significant share of all

employment-related complaints.

• Retaliation complaints accounted for more than 50 percent of all charges filed

with the EEOC.

• Retaliation complaints made up between 11 and 26 percent of employment-

related complaints submitted to CRD for investigation.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | OCT. 2022

10

See Table 1 for more details on retaliation complaints submitted to the EEOC, RCI, and CRD

based on publicly available data.

Table 1.

Retaliation Complaints Submitted in California, 2017-2020

Agency

2017

2018

2019

2020

US Equal

Employment

Opportunity

Commission

6

2,752

(50.7% of all

state charges)

2,183

(50.3% of all

state charges)

2,319

(54.2% of all

state charges)

2,306

(55.8% of all

state charges)

Retaliation

Complaint

Investigation Unit

within California

Labor

Commissioner’s

Office

4,178

7

5,633

8

6,515

9

5,334

10

California Civil

Rights Department

1,094

11

retaliation

complaints for

investigation

(11% of all

employment

complaints)

2,785

12

retaliation

complaints for

investigation

(26% of all

employment

complaints)

2,717

13

retaliation

complaints for

investigation

(19% of all

employment

complaints)

8,468

14

retaliation

basis in

complaints

seeking a

right-to-sue

17,697

15

retaliation

basis in

complaints

seeking a

right-to-sue

13,181

16

retaliation

basis in

complaints

seeking a

right-to-sue

TOTAL

16,492

28,298

24,732

Total (2017-

2020): 69,522

II. Workers Cite Concerns about Employer Retaliation and the

Threat of Job Loss As Major Reasons for Not Reporting

Employer Violations

Even as state enforcement agencies receive tens of thousands of retaliation complaints per

year, our survey findings and previous research in California reveal that filed complaints are

just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to workplace violations and retaliation. Of the

almost one in two California workers who experienced violations but did not report them, a

majority (96 out of 179) indicated that concern about retaliation was a deterring factor.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

11

More than 4 out of 10 survey respondents reported that concern about employer

retaliation has possibly stopped them from speaking up about dangerous or unhealthy

working conditions in the past. Black and Latinx workers were more likely than white

workers to say that this was the case. Forty-nine percent of Black workers and 45 percent

of Latinx workers indicated this was their experience, compared to 39 percent of white

workers. Finally, more than half of working Californians (51 percent) said that concern

about employer retaliation would influence their decision about whether or not to report a

workplace violation in the future. These results show that retaliation concerns keep many

workers from coming forward. Previous California worker surveys have presented similar

findings.

17

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

12

III. Given Widespread Economic Precarity in California, Retaliatory

Firings Can Have Catastrophic Consequences for Workers

Members of the Pilipino Association of Workers and Immigrants described in focus group

conversations that their economic needs and the need to have a job keep them in jobs

where their rights are violated and where they endure conditions harmful to their health:

“Even if it isn’t true, employers say that if you go to the Labor Commission, you won’t be

able to find a job. The employers have an association and have a blacklist of workers who

filed claims.”

“We are not even paid the minimum wage, but we have tons of bills to pay. We don’t have

medical insurance. Our priority is remitting money back home, but, with low wages and

bills, we don’t have much money to send home. We end up having to take second and third

jobs. We end up getting sick. When I was 40, it wasn’t so bad, but now that I am 50, I have

back pain and neck pain.”

18

With many workers just a paycheck or two away from not being able to pay their bills, the

real threat of being fired or having pay or hours cut can factor heavily in a worker’s decision

about whether to come forward with concerns.

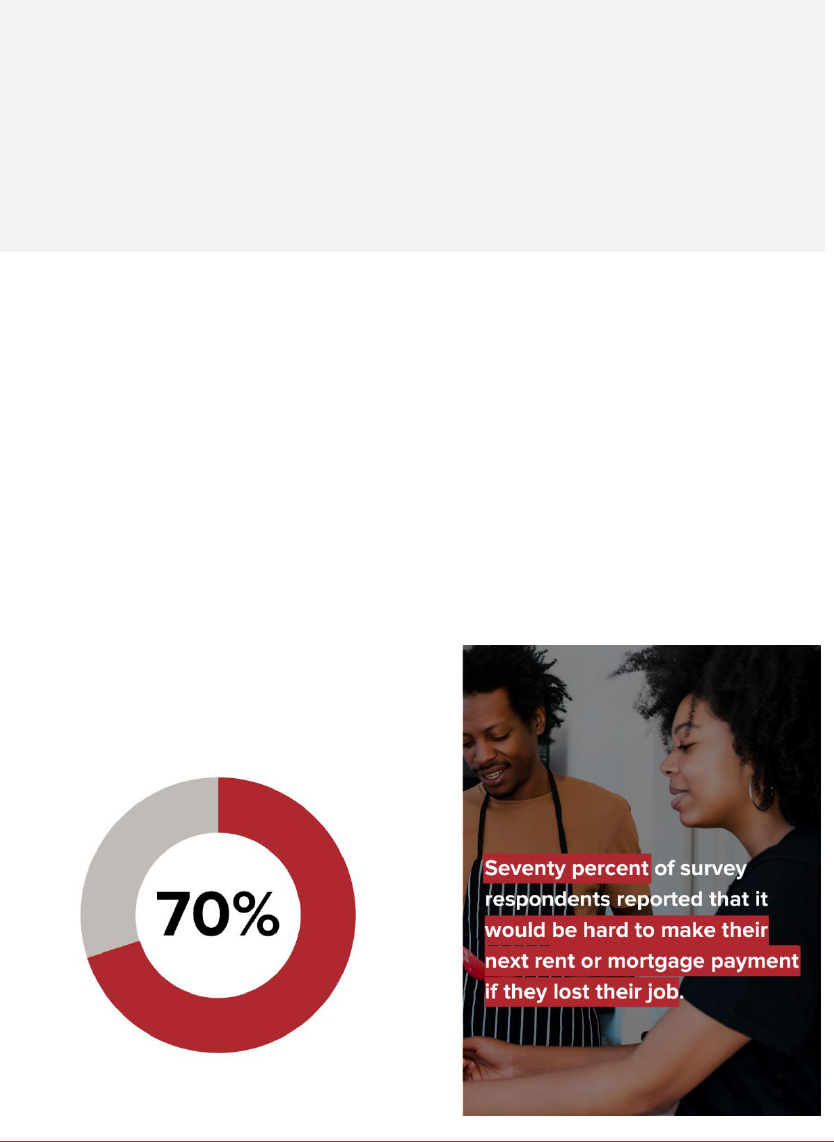

Our survey found that 40 percent of the California workforce would be unable to cover a

month or less of regular expenses if they lost their job. Seventy percent reported that it

would be hard to make their next rent or mortgage payment, with nearly half of those

reporting that it would be “very” hard.

Among survey respondents who had prior job losses, 79 percent also reported significant

economic hardship from those job losses, including not being able to pay bills on time (40

percent), seeking food from a food bank (20 percent), delaying health care or medication

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

13

(22 percent), and using all their savings (36 percent).

These survey results are consistent with numerous other reports detailing the economic

insecurity of California’s workforce. For example, according to the California Future of

Work Commission’s March 2021 report, the majority of renter households in the state pay

more than 30 percent of their income toward housing.

19

According to the Northwestern

Institute for Policy Research and the California Association of Food Banks, about one in

every five Californians experiences food insecurity, meaning that they “do not know where

their next meal will come from — with greater levels of hunger experienced by Black and

Latinx families.”

20

According to a Public Religion Research Institute study of California

workers, almost half (47 percent) of California workers struggle with poverty, and they are

more likely to be Latinx workers (60 percent of Californians who work and struggle with

poverty are Latinx).

21

Workers in California and across the country lack adequate emergency savings that could

help them weather even a brief interruption in work. For example, a 2019 AARP national

study found that 53 percent of households do not have an emergency savings account and

highlighted how “people of color in the United States face a massive wealth gap compared

to whites, and women have significantly less wealth than men.”

22

It cited a Federal Reserve

finding that “the median [B]lack family had just $3,600 in household wealth in 2018, the

median Latino family had $6,600, and the median white family had $147,000.”

23

In 2018,

the Federal Reserve reported that 4 in 10 adults would have difficulty covering a

hypothetical unexpected expense of $400.

24

More broadly, the Federal Reserve found that

3 in 10 adults are “either unable to pay their bills or are one modest financial setback away

from hardship.”

25

Making matters worse, most California workers lack access to a meaningful safety net if

they lose their job or part of their income.

First, while severance pay policies can sometimes provide some immediate financial

support for workers who are laid off or who voluntarily resign, most workers across the

income spectrum do not have access to such pay. Our survey found that only 14 percent of

California workers who had lost jobs received severance pay after every job loss. Sixty-four

percent of workers who lost jobs have never received severance pay.

Second, while an essential program, California’s unemployment system does not offer

workers reassurance that they can obtain quick and meaningful economic support in case

of job loss. California workers may receive a maximum of only $450 per week in

unemployment benefits. The California Budget & Policy Center has illustrated how that

amount falls far short of what California workers need to support their families and look for

work.

26

For “the majority of California renters with low incomes who spend at least half of

their income on rent,” current benefit levels mean that they would have to spend their

entire unemployment benefit to pay rent alone without other income.

27

In addition, as the

COVID-19 pandemic has starkly exposed, the California unemployment system is plagued

by outdated infrastructure, long delays for benefits, abrupt suspensions, and concerns

about fraud.

28

Even if the system worked efficiently for workers, a successful application for

benefits still relies on employers “to exchange information that is necessary in determining

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

14

eligibility” with the Employment Development Department.

29

Workers who have been fired

in retaliation will not generally expect their employer to cooperate with a request for

unemployment assistance. Employers may even falsely report that a worker was fired for

misconduct, making a worker initially ineligible for unemployment benefits and forcing

them to appeal the denial, delaying benefits even longer. Furthermore, undocumented

immigrant workers remain ineligible for unemployment benefits.

30

This economic precarity heavily influences whether workers decide to raise workplace

concerns, especially in an employment-at-will framework where employers can fire

workers without cause and in an environment where protections against retaliation are

inadequate and do not mitigate the immediate financial harm that comes with being fired,

demoted, blacklisted, or otherwise punished for coming forward.

IV. California’s Anti-Retaliation Laws Fall Short Because They Force

Workers to Bear Significant Financial Risk Before Holding

Employers Accountable

A 2019 NELP 50-state survey of anti-retaliation laws tied to the reporting of minimum wage

or other wage-theft violations showed that California is one of a handful of states where

the statutes include provisions that NELP considers minimally necessary to help deter

retaliation and provide meaningful remedies for workers: a private right of action; state

monetary penalties; attorneys’ fees and costs for workers who file lawsuits; and both

compensatory and punitive damages for workers.

31

The California Labor Commissioner

alone is charged with enforcing over four dozen anti-retaliation statutes.

32

One of those

relatively strong statutes is California Labor Code Section 98.6, which requires employers to

pay up to $10,000 in penalties to workers who suffered retaliation, and Labor Code Section

1102.6, which shifts the burden of proof under Labor Code 1102.5 (the whistleblower

statute) to the employer to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that there was a

legitimate, independent reason for the adverse action.

33

And a number of other California

statutes stand out nationally, such as those that expressly prohibit various forms of

immigration-based retaliation

34

and do not require an adverse action and the recent 2017

amendment (SB 306) that allows the Labor Commissioner to seek a preliminary court

injunction to stop retaliation with “reasonable cause” to believe a discrimination or

retaliation violation has occurred.

35

These types of valuable tools should continue to form

key components of any effort to fight retaliation.

However, despite various strengths, none of California’s anti-retaliation laws provide

workers who experience retaliation with monetary relief when they need it most:

immediately or soon after an employer retaliates.

After experiencing retaliation, a worker must generally file a new complaint alleging

unlawful retaliation. At that point, the worker assumes a difficult legal burden of proving

that retaliation happened,

36

and retaliation investigations and litigation can take months or

years before reaching a final decision. The CRD reported in 2019 that even after reducing

the average number of days for the agency to close a case, the 2018 average was still 109

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

15

days.

37

In 2018, more than 6,000 CRD cases experienced a wait of 30 days or more just to

complete the intake interview.

38

A FY 2019 report on California’s Occupational Safety and

Health program performance found that the California Division of Labor Standards

Enforcement completed only one percent of its investigations within 90 days and that the

average number of days for investigation completion was 582.

39

The EEOC informs

complainants that the agency takes “approximately 10 months to investigate a charge.”

40

And even when a court or agency finally orders an employer to pay a worker monetary

damages after retaliation, getting an employer to actually pay the judgment presents its

own challenge.

41

In sum, by the time a worker obtains any relief from a retaliation investigation or lawsuit in

California (if they do at all), a worker who was fired for reporting a violation or whose

employer reduced their pay (e.g., by cutting hours or assigning a worker to a less desirable

shift with fewer tip earnings) has suffered potentially devastating and long-term economic

consequences. When workers across the state generally have little or no job security and

most cannot afford even a $400 emergency, one missed or reduced paycheck can quickly

snowball into a missed rent or mortgage payment; eviction; cut utilities; an inability to

provide food, medicine, or school supplies for their children; a reduced credit score; late

fees; unpaid child support or unpaid traffic fines with their own punitive repercussions; and

more. This economic risk compounds the other serious risks that workers face when

asserting their rights. When an employer retaliates, workers often endure painful

emotional distress, ongoing harassment, or other unfair treatment at work. And workers

who face detention or deportation because their employer reported them to immigration

authorities experience uniquely traumatic consequences and potentially permanent

separation from their families and community.

V. Unjust and Arbitrary Firings: California’s At-Will Employment

System Creates an Enormous Power Imbalance Between

Workers and Employers, With Far Reaching Consequences

in the Workplace and Beyond

A. At-Will Employment Allows Employers to Fire Workers for Almost Any Reason or No

Reason at All

One major reason that California workers lack strong protection from retaliation is that

employers can generally fire workers for any reason or no reason at all, unless otherwise

explicitly prohibited by law. Without protection from arbitrary and unfair firings, workers

have a much harder time speaking up on the job and enforcing their rights.

42

And even

when the law prohibits retaliatory firings for workers who file complaints with government

agencies or organize at their workplaces, employers can easily deny that firings are

motivated by retaliation and point to any other arbitrary reason as the impetus for firing.

The US is unique among industrialized nations in that employees can be fired abruptly—without

notice, a chance to address employment problems, or even a stated reason—and left with bills

due and no paycheck or severance pay. By contrast, Australia, Brazil, Japan, Mexico, the United

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

16

Kingdom, and most of the European Union, among many other countries, require employers to

provide workers with a sufficient reason for termination.

43

In the US, employment termination policies are generally regulated by state jurisdictions.

Currently in California, employment is presumed to be at-will, meaning that an employer may

discharge a worker at any time, without any reason or cause so long as no other law or

employment contract is violated.

The at-will employment doctrine that allows employers to legally fire workers without

warning or explanation was not determined through any democratic legislative process.

Instead, conservative judges gradually imposed the doctrine through judicial rulings in the

decades following the passage of the 13th Amendment, which banned slavery and most

forms of servitude.

44

A century and a half later, at-will employment still underpins the power imbalance

between employers and workers. While both workers and employers take on a certain

amount of risk when they enter an employment relationship, workers take on greater risk

because their livelihood is at stake. In addition to not needing to give advance notice or

justification for termination, employers also do not have to set clear performance

standards, apply rules or expectations consistently, or even inform workers of how

discipline or termination decisions are made. This stymies complaint-driven enforcement of

workplace laws because workers have to weigh any action they take against the possibility

of discipline and termination.

Lack of job-security protections also compounds the negative effects of systemic racism in

the workplace and the labor market. Workers of color—especially Black and Latinx

workers—face widespread systemic racism and segregation in the workplace and labor

market, including a high prevalence of discrimination in the hiring process, on the job, and

in disciplinary matters.

45

These circumstances mean that workers of color must contend

with heightened challenges in an at-will employment system. Black workers—who are the

“last hired, and first fired”—especially bear the brunt of the job insecurity caused by at-will

firings.

46

Our survey of the California workforce provides insight into unfair firings in the state,

revealing how widespread the problem is and the many negative impacts for workers,

families, and communities.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

17

B. Unfair and Arbitrary Firings are Common

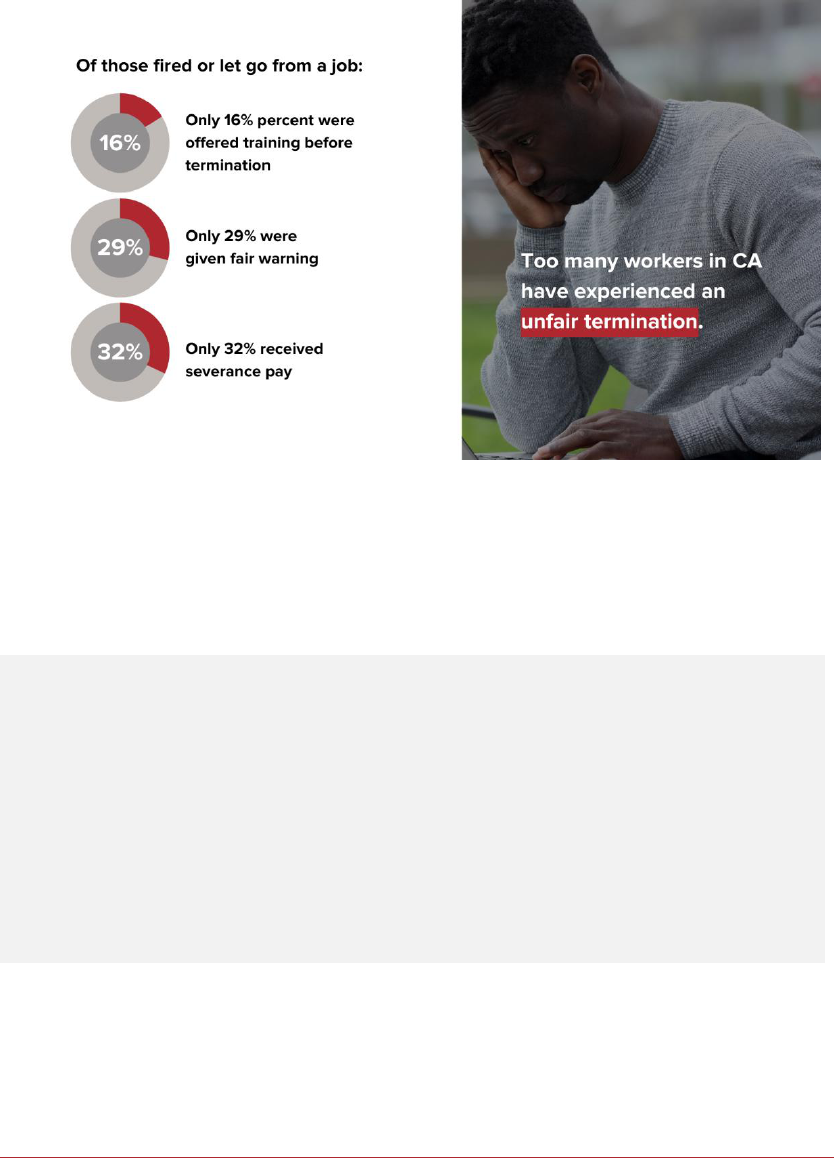

Our findings show that an alarmingly large share of workers in California have experienced

an unfair termination. More than 4 in 10 California workers have been fired or let go from a

job at some point, and only 29 percent of those workers were given fair warning.

Of workers who were fired or let go, just 16 percent said they were offered more training

before termination. And fewer than one in three received severance pay.

A participant in the focus groups conducted with members of the CLEAN Carwash Worker

Center described an experience of being fired after taking part in an investigation:

“I worked at the [NAME OF EMPLOYER WITHHELD] for several years. During my time there

an investigation began by the state of California to look into the conditions of work at the

business. At this car wash, we did not have fixed hours of work. We were asked to arrive

early and wait in an alley for work, sometimes for hours. We were never paid for this time. I

was one of the worker leaders during the time and always shared what was happening at

the car wash with the investigators. That was why they fired me on [DATE WITHHELD].

When that happened, I asked my manager why he was firing me. He said it was simply

because there was no longer work for me. But they always told me that I was one of their

best workers. I came back the next day and said, ‘Did you fire me for speaking up on the job,

for standing up for my rights, and fighting to improve the work conditions here?’ But of

course, he only repeated that I was no longer needed at the car wash.”

47

Workers are aware that there is a risk of being fired anytime, even if not filing a formal

complaint. When describing what she feels about work, one participant in a focus group

with members of the Pilipino Worker Center said:

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

18

“For me, what I think about and bothers me is that our employer can fire us at any time

they want to. What’s more they have favoritism. That, I worry about.”

48

C. At-Will Employment Coerces Workers into Accepting Harmful and Illegal Working

Conditions

At-will firings enable employers to use the threat of termination as a form of economic

coercion. Under the at-will system, if workers fear the threat of unfair discipline or

dismissal from managers, they will be more likely to accept low pay, unfavorable terms of

employment, and poor working conditions; this is especially true for those with the least

power in the labor market. Some may also feel pressure to accept illegal situations such as

wage theft or health and safety hazards. Even if employers are not violating any actual

laws, at-will employment can create pressure for workers to behave in ways that are

detrimental to their well-being, such as deprioritizing their health needs, consenting to

undesired overtime hours, refraining from taking time off, or enduring verbal abuse.

Our survey bears this out, with a significant share of California workers reporting pressure

in their workplace to accept harmful and even illegal working conditions. Seventy-three

percent of respondents worked while sick to avoid being fired. Forty-three percent

reported that an employer pressured them to accept wage theft, or that they worked extra

hours without pay to avoid being fired. More than a third (34 percent) of workers accepted

pay that was less than what they were owed to avoid being fired.

Additionally, 39 percent of workers reported experiencing hazardous or unsafe working

conditions, and 35 percent reported working at a dangerous or unreasonable pace,

because of concern about possibly losing their jobs. Almost half (47 percent) of workers

have endured verbal hostility from a manager or supervisor without saying anything, and

two out of three workers (68 percent) also reported skipping breaks to avoid being fired.

More than half of respondents (53 percent) reported not asking for pay increases or

benefits they felt they deserved for fear of job loss. Forty-two percent said that termination

concerns also silenced them from speaking up about dangerous and unhealthy working

conditions. And more than 40 percent of workers—including 46 percent of Latinx workers

and 55 percent of Black workers—said that concern about being fired or disciplined may

have prevented them from joining with their co-workers to push for job improvements.

These findings show in vivid detail how at-will employment goes hand in hand with

exploitative working conditions. As one caregiving worker explained in a Pilipino Worker

Center focus group:

“If you complain, the agency will tell you, ‘Okay, will you like us to get another caregiver?

Because either you like it or not. You do the job, we’re going to pay you. That’s it. If you

cannot do the job, we’re going to find another one.’”

49

A sushi delivery driver in a focus group conducted by the Chinese Progressive Association

described being fired simply for raising a question about a delivery route:

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

19

“I’d have to deliver from the warehouse to pick up sushi from South San Francisco, then

deliver in San Francisco and Berkeley and Alameda County. The route takes a lot of time to

deliver. I didn’t complain to the employer, but in the last week of my job, my route included

delivery to San Jose. It didn’t make sense since it was a different direction from my route,

and I told my employer. He wasn’t happy with what I told him. The next day he didn’t give

me a work schedule. The employer pretty much fired me. That day the boss told me to

return the company car keys, and I will send someone to go to your home to retrieve the

car. (Did they give any explanation why you were fired?) No.”

50

People who have been formerly incarcerated by the US’s anti-Black criminal legal system

experience particular employment pressures that often cause them to accept poor working

conditions. Probation, parole, and other court-surveillance and supervision programs

regularly mandate maintaining or seeking employment as a standard set of conditions to

remain free from incarceration. Twenty-five percent of state prison admissions are due to

“technical rule violations” of parole.

51

Technical rule violations are not allegations of a new

criminal offense but are violations of parole rules that regularly include passing alcohol

and/or drug tests; satisfactory payment of criminal justice debt; completing court-

mandated classes; maintaining curfew; and seeking and maintaining employment.

52

This

threat of reincarceration drives many court-surveilled workers to enter and remain in jobs

with depressed labor standards and to avoid speaking up about illegal working conditions.

VI. Policy Recommendations: A Retaliation Hardship Fund,

Consistency Across the Labor Code, and a State “Just Cause”

Standard

California’s current legal system for handling workplace violations demands too much from

workers and fails to curb widespread wage theft, discrimination, and unsafe and unfair

working conditions. The state can more effectively support workers by addressing arbitrary

firings, retaliation, and the financial consequences of employer retaliation.

A. Create a Retaliation Fund to Provide Workers with the Financial Support They Need

When an Employer Retaliates

California lawmakers should address the critical gap in today’s anti-retaliation laws that

leaves workers without economic support when they need it most, through a state-funded

retaliation fund.

A retaliation fund would allow a worker who has reported a workplace violation to a state

agency to access quick, meaningful, and one-time financial assistance if their employer

retaliates against them (e.g., by firing, cutting pay or hours, demotion, blacklisting, etc.).

The fund would directly fill the urgent gap left by California’s existing anti-retaliation

statutes, under which it can take months, if not years, for a worker to obtain financial

support and a final decision on a retaliation complaint. The fund could draw on state

general funds for an initial period of time and eventually be funded through penalties

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

20

collected from employers who are found to have retaliated unlawfully.

The concept of a retaliation fund is not new. As NELP outlined in a 2021 report on

retaliation funds, worker organizations have long used different types of mutual support

funds to assist workers in exercising their rights.

53

California also already operates

restitution funds for garment

54

and car wash workers

55

who are unable to obtain the

compensation they are owed by employers through the legal system.

Such a fund could encourage significantly more workers to come forward with workplace

violations. Our survey found that for more than two in three California workers, access to a

retaliation hardship fund could help them report a future violation to a government

agency. And an overwhelming majority of working Californians—92 percent—support the

establishment of a retaliation hardship fund that would provide one-time financial

assistance to workers who file good-faith complaints about employer retaliation. Appendix

A outlines how such a fund in California could be structured and function.

B. Simplify California’s Anti-Retaliation Laws to Help Workers Understand and Assert

Their Rights

Lawmakers should create consistency across the state’s Labor Code provisions addressing

retaliation so that workers can more easily understand and enforce their rights. As part of

this process, lawmakers should consistently apply existing laws that presume any harmful

action an employer takes against a worker within 90 days after the worker asserts a basic

workplace right is retaliation. For example, under existing law, California employers are

presumed to have committed retaliation within 90 days and must prove otherwise in the

warehouse and fast-food industry, as well as when their actions include immigration-

related threats.

56

Lawmakers should also ensure that any penalties paid by employers, such

as the up to $10,000 penalty for retaliation, goes to the worker rather than to the general

fund.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

21

California’s laws need to be strongly worded and strongly enforced. When workers file

complaints of retaliation with the Labor Commissioner’s office, they should feel confident

that their claims will be handled with the appropriate urgency. Unfortunately, despite

increases in funding in the 2022 state budget, the Labor Commissioner’s Retaliation

Complaint Investigation Unit is still under-resourced, which creates challenges for enforcing

the more than 45 labor laws and resolving its large backlog of cases. Lawmakers should

substantially increase funding for the Retaliation Complaint Investigation Unit, which

receives considerably less funding than the Labor Commissioner’s Office Wage Claim

Adjudication unit and the Bureau of Field Enforcement.

C. Adopt a State “Just Cause” Law to Protect Workers from Unfair and Arbitrary Firings

Our survey found that a large majority—81 percent—of working Californians of all parties

support the adoption of laws protecting workers from unfair and arbitrary firings. Replacing

California’s at-will firing system with a just-cause termination standard would require

employers to provide legitimate reasons and fair warnings before terminating workers.

Effective just-cause policies also require employers to notify workers of performance

problems in advance and provide an opportunity to address them. And, when workers are

fired, such policies guarantee severance pay or, if they were terminated without just cause,

a right to reinstatement. Finally, by requiring a good reason for terminations, just-cause

protections more effectively protect workers from retaliation when they insist on other

workplace rights. Appendix B outlines the key provisions a California just-cause law should

contain.

VII. Conclusion

The wellness of individual workers, their families, and their communities depends on their

ability to thrive inside and outside of work. That is only possible when workers can fully

exercise and enforce their workplace rights without concern for losing their jobs. Current

California laws, however, perpetuate a deep power imbalance between workers and their

employers that forces workers into harmful, unjust, and unstable working conditions. This

power imbalance stems from unjust and arbitrary firings permitted under California’s at-

will employment system, rampant retaliation by employers, and economic insecurity.

California workers simply have too much to lose if they raise concerns at work or report

violations, despite existing anti-retaliation laws. A just-cause standard to end unfair firings,

in addition to a retaliation fund to provide immediate economic support for workers

contesting retaliatory job actions, would put California’s workers on much stronger footing

to demand better workplace conditions and to hold employers accountable.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

22

Appendix A – Key Elements of a Retaliation

Fund

What is a retaliation fund?

• A retaliation fund allows a worker who has filed a wage-theft or other complaint

with a state agency to access quick and meaningful financial assistance when their

employer fires them or cuts part of their pay because of that complaint.

• Retaliation funds directly fill the urgent gap left by California’s existing anti-

retaliation statutes under which it can take months, if not years, for a worker to

obtain a final decision on a retaliation complaint.

• Retaliation funds are not entirely new. As NELP outlined in its 2021 report on

retaliation funds,

57

worker organizations have long used different types of mutual

support funds to aid workers in exercising their rights.

• A variety of public and private economic hardship funds have played an important

role in supporting workers and families. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for

example, cities and states like Boston, New York City, Atlanta, San Antonio, Tucson,

and Washington, DC established hardship funds to support impacted individuals

and families.

58

Prior to the pandemic, states and localities proved that

governments could establish funds to provide financial support to workers and

others in a wide range of contexts. The federal Emergency Food and Shelter

Program, for example, distributes funds to local governments that, in turn,

distribute the funds to private nonprofit organizations who provide financial

assistance to individuals facing economic hardship.

59

All states, including California,

operate a compensation fund to provide financial support to victims of crime.

60

• California also funds and operates restitution funds for garment

61

and car wash

workers

62

who are unable to obtain the compensation they are owed by employers

through the legal system. (Maine and Oregon operate similar funds for workers

that are not industry specific.) In addition, California law has established the Travel

Consumer Restitution Corporation, a fund to help California consumers who “suffer

losses as a result of the bankruptcy, cessation of operations, insolvency, or material

failure of a seller of travel to provide. . .transportation or travel services

contracted.”

63

»

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

23

What kind of retaliation would the retaliation fund cover?

• A worker would be able to receive financial support from the retaliation fund if

their employer fired them or reduced their pay in any way because the worker filed

a complaint about the employer with a state agency. The retaliation fund must

define “adverse actions” broadly given the countless and often subtle ways in

which employers retaliate. At a minimum, an “adverse action” that results in losing

one’s job or pay should include the following:

o firing a worker

o constructive discharging (where the employer creates a work

environment that forces a worker to leave the job)

o demoting a worker

o blacklisting that keeps a worker from finding a new job

o reducing hours

o changing schedules in a way that impacts income

o making immigration-based threats that force a worker to leave the job

o reducing pay in other ways

How much support should a worker recover from the retaliation fund?

• A worker should be able to obtain a one-time financial assistance payment from the

retaliation fund. This arrangement can draw from existing hardship models where one-

time payments are not considered taxable income, making it easier for agencies to

administer.

• In California, workers should be able to obtain at least $2,500 as a one-time payment.

• The primary objective in setting the amount of financial assistance available to workers

through a retaliation fund is to ensure that financial support can meaningfully help sustain

a worker while searching for a new job, processing their retaliation complaint, and

responding to the financial and related consequences of losing a job or part of their pay

due to retaliation.

How would a retaliation fund be funded?

• A California retaliation fund could be funded for an initial period of time with state general

funds. The state can divert penalties for retaliation to maintain the retaliation fund in the

future.

• Workers should not have to repay financial support received through the fund. The

burden of repaying into the fund should fall to employers who are found to have

retaliated unlawfully.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

24

• When a worker receives financial support from the retaliation fund, if the worker’s

employer is found to have unlawfully retaliated after a full investigation or court decision,

the employer should be required to replenish the fund with three times the amount of

financial support that the worker received. This would be similar to the way a growing

number of states and cities, including California, require employers to pay treble (i.e.,

three times) damages for wage theft.

How would workers access the fund? Who would be eligible?

• Accessing financial support from a retaliation fund should be as simple as possible in order

to provide support to a worker immediately after they lose their job or part of their pay

due to retaliation.

• The following steps can help ensure quick access to meaningful financial support:

o Step 1. A worker files a complaint with a state labor-enforcement agency alleging an

employer violation (e.g., the worker submits a wage-theft complaint to the Labor

Commissioner).

o Step 2. The state labor-enforcement agency that receives a worker’s complaint sends

a notice of the complaint to the employer(s) named in the complaint, or the agency

obtains evidence that the employer became aware of the complaint filed.

o Step 3. If the employer fires the worker or reduces the worker’s pay in what the

worker reasonably believes amounts to retaliation for filing their complaint, the

worker submits a good-faith complaint alleging retaliation to the labor-enforcement

agency charged with administering the retaliation fund within 90 days of the alleged

retaliation along with a request for financial support from the fund.

o Step 4. The agency that administers the retaliation fund will review the request for

financial support and issue a one-time payment to the worker as soon as possible.

Critically, a worker should not have to wait until an investigation or court case

determines whether retaliation occurred, because that takes months, if not years,

and the delay would defeat the purpose of the fund: to provide support when a

worker needs it most. In implementing a retaliation fund, the implementing agency

must seek to support the worker when a worker has alleged retaliation in good faith.

What safeguards can help avoid potential misuse?

• While nothing should suggest that the proposed retaliation fund would be vulnerable to

misuse by workers, some safeguards can assuage potential doubts:

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

25

o The fund should only be available to workers who have filed a complaint with a labor-

enforcement agency. Agencies can retain their existing discretion over whether to

investigate each and every complaint.

o If, in the course of an investigation, a worker is found to have intentionally lied or

fabricated evidence, the agency administering the retaliation fund could revoke that

worker’s eligibility for all future support from the fund.

What is the role of community partnerships in successful implementation of a fund?

• Worker leaders, advocates, academics, and others with experience addressing wage-

theft and other violations have long emphasized the need for enforcement agencies to

form close partnerships with local, community-based organizations. In establishing a

retaliation fund, California lawmakers should also ensure that the fund administrator can

engage effectively with community organizations to successfully implement the fund,

including through grants and formal agreements that allow community-based groups to

conduct outreach, educate, help process complaints and requests for financial support,

and so on.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

26

Appendix B – Key Provisions of a “Just

Cause” Law

1. Good reason for discharge – The core of a just-cause employment system is a

requirement that the employer must show that there is a justifiable reason for

discharging a worker, such as poor work performance that does not improve after

feedback and coaching, violation of important employer policies, or employee

misconduct. Just-cause systems also allow employers to discharge workers for

bona fide economic reasons, such as when business declines or a position is no

longer needed, without a need to show just cause.

2. Duty on the employer – Under a just-cause system, the employer is responsible for

demonstrating a good reason for discharging the worker—the reverse of the

current system, where employees must demonstrate that a firing was for an

impermissible reason. Shifting that responsibility to the employer is widely

recognized as key for protecting workers against arbitrary and unfair firings,

including against firings that are currently illegal but where workers have difficulty

enforcing their rights, such as in cases of racial discrimination or retaliation against

whistleblowers.

3. Certain activities are categorically protected – Just-cause legislation should also

clarify that certain reasons are categorically not grounds for discharge. Examples of

categorically protected employee activities should include: (1) communicating to

any person, including other employees, government agencies, or the public about

job conditions; and (2) refusing to work under conditions that the employee

reasonably believes would expose them, other employees, or the public to an

unreasonable threat of illness or injury on the job.

4. Fair notice to workers and opportunity to address problems – Another key

component is fair notice to the worker of any performance problems and the

opportunity to address them before being discharged. This process, which is often

called “progressive discipline,” is well established. It also mirrors the process that

many responsible employers already use: giving employees feedback and coaching

on performance issues and support in addressing them before getting to the point

of possible discharge. However, a just-cause policy should make clear that certain

kinds of serious misconduct may trigger a bypass of the progressive discipline

process and allow for immediate employer action. These should include conduct

that threatens the safety or well-being of other people, such as violence or

harassment.

5. Equal coverage of temp and staffing employees – Economic theory suggests that if

it becomes more difficult for employers to discharge workers, they will shift

employment to temp and staffing agencies because such employees are generally

»

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

27

not subject to the same standards. Therefore, it is crucial that just-cause

employment protections apply equally to employees working through temp or

staffing agencies. A just-cause policy should expressly address these issues—for

example, by requiring the same showing of just cause for ending employment.

6. Limits on defined-term employment – Another key consideration for a just-cause

policy is under what circumstances to allow employers to hire workers for defined

projects or terms, after which their employment can end without a need to

demonstrate just cause. Examples of reasonable defined-term employment might

include short-term, seasonal jobs in industries that need additional staffing during

certain times of the year, and projects for which the need for employees or the

funding to pay them will end once the project is completed. However, it is

important that such authorization for defined-term employment be limited to

clearly defined circumstances that prevent it from becoming a loophole through

which employers can meet ongoing staffing needs. In addition, during the course of

such defined-term employment, just-cause protections against early discharge

should apply.

7. Protections to ensure economic discharges are not a loophole – It is important to

ensure that economic (i.e., non-performance-based) discharges, when they are

necessary, do not become a means for sidestepping just-cause protections.

Employers should be allowed to make economic discharges when business

conditions warrant, but there should be standards for demonstrating their

necessity to ensure they are not used to disguise otherwise impermissible

discharges.

8. Protections against intensive surveillance and monitoring – Just-cause legislation

is an opportunity to begin to address the harmful and discriminatory impact of

employers’ growing use of electronic surveillance, algorithmic decision-making,

and automated employee evaluation systems. Electronic monitoring and decision-

making can result in employees being disciplined and even discharged with little

human involvement in those assessments. Pervasive monitoring of workers also

means that minor infractions can easily be found and used to sidestep just-cause

protections. Just-cause legislation should limit the use of data collected through

electronic monitoring for termination and disciplinary decisions.

9. Severance pay – When workers are discharged—whether for just cause or

economic reasons—providing severance pay is crucial for mitigating the very

harmful economic impacts of job loss. Without severance pay, workers and families

face dramatic income cuts and extreme hardship, including being unable to pay

rent or a mortgage, potentially leading to eviction or foreclosure. To provide

workers with a cushion as they search for new employment, just-cause protections

should guarantee a basic period of severance pay, such as four weeks.

Guaranteeing severance pay is not only fair and broadly popular, but it also avoids

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

28

the common employer practice of pressuring workers to sign away their rights in

exchange for receiving severance pay.

10. Strong remedies and relief – A just-cause policy should include strong remedies for

violations, including the right to reinstatement and money damages, together with

additional penalties or liquidated damages that are sufficient to deter

noncompliance. Money damages must reflect the full scope of damages that

workers face. Without such meaningful sanctions for discharges without cause, any

new just-cause policy would not achieve the goal of ensuring fair process before

workers are subjected to job loss.

11. Effective enforcement vehicles, including qui tam – Government labor agencies

simply do not have the capacity to adequately enforce employment protections on

their own. Therefore, a just-cause policy should include effective tools to allow

workers to bring enforcement actions on their own. These should include a private

right of action, authorization for recovery of attorneys’ fees, and authorization for

“qui tam” enforcement. Similar to a private right of action, qui-tam enforcement

allows workers and members of the public to supplement government agency

enforcement by stepping into the government’s shoes to bring enforcement

proceedings as “private attorneys general.” Significantly, it can allow

representative organizations, such as unions or worker centers, to bring

enforcement action, ensuring that the burden of challenging employer lawbreaking

does not remain solely on individual workers, who may face retaliation.

12. No waivers of rights permitted – A just-cause policy should provide that workers’

rights may not be waived through private agreements absent court or Department

of Labor supervision and explicitly prohibit employers from requiring workers to

enter into a private agreement to waive their just-cause and whistleblower rights.

13. Rights that are enforceable before judges and juries, regardless of forced

arbitration requirements and class/collective-action waivers – Finally, a just-cause

policy should ensure that its protections can be enforced by workers before judges

and juries. Forced arbitration requirements deny workers the right to go before a

judge and jury when their employer breaks the law. Instead, workers must bring

any claims to a secret proceeding before a private arbitrator who is not

accountable to the public. Because these arbitrators depend on corporations for

repeat business, they strongly favor employers. Making matters even worse, class

and collective-action waivers routinely incorporated into these requirements

prevent groups of employees from banding together to challenge employer

lawbreaking. An effective just-cause policy must ensure that forced arbitration

requirements and class/collective-action waivers will not interfere with the ability

of workers to enforce their rights under that policy.

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

29

Appendix C – Survey Methodology

Between January 7 and January 23, 2022, YouGov interviewed 1,152 respondents through

an online survey. The respondents were then matched down to a sample of 1,000 to

produce the final dataset. Respondents were collected as part of a California state

representative sample as well as California resident oversamples of Black and Latinx

respondents.

The respondents were matched to a sampling frame representing employed residents

between 18 and 64 years of age. The sampling frame consisted of interlocking parameters

of gender, age, race, and education. The frame was constructed by stratified sampling from

the full 2020 Current Population Survey sample with selection within strata by weighted

sampling with replacements (using the person weights on the public use file).

The matched cases were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores. The

matched cases and the frame were combined, and a logistic regression was estimated for

inclusion in the frame. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity,

years of education, and region. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the

estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles.

The weights were then post-stratified on a four-way stratification of gender, age (4-

categories), race (4-categories), and education (4-categories), to produce the final weight.

The margin of error for the entire survey is ±3.6%

»

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

30

Endnotes

1

California Coalition for Worker Power (CCWP)

Focus Group with California members of Fight for 15

and a Union, in Spanish, held in September 2021. On

file with author.

2

Chinese Progressive Association and Asian

Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus,

Press Release, August 21, 2021,

https://cpasf.org/updates/workers-at-popular-

chinatown-restaurant-win-1-61-million-in-massive-

wage-theft-settlement/.

3

“Overview,” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, accessed November 2, 2021,

https://www.eeoc.gov/overview.

4

“Laws that Prohibit Retaliation and

Discrimination,” California Department of Industrial

Relations, accessed November 2, 2021,

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/HowToFileLinkCodeS

ections.htm.

5

Kevin Kish, 2019 Annual Report, Department of

Fair Employment and Housing,

https://www.dfeh.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/32/2020/10/DFEH_2019An

nualReport.pdf.

6

“FY 2009 – 2020 EEOC Charge Receipts for CA,”

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

accessed October 29, 2021,

https://www.eeoc.gov/statistics/enforcement/char

ges-by-state/CA.

7

Julie A. Su, 2017 Retaliation Complaint Report

(Labor Code §98.75), State of California Department

of Industrial Relations,

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/RCILegReport2017.pd

f.

8

Patricia K. Huber, 2018 Retaliation Complaint

Report (Labor Code §98.75), State of California

Department of Industrial Relations,

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/RCILegReport2018.pd

f.

9

Lilia García-Brower, 2019 Retaliation Complaint

Report (Labor Code §98.75), State of California

Department of Industrial Relations,

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/RCILegReport2019.pd

f.

10

Lilia García-Brower, 2020 Retaliation Complaint

Report (Labor Code §98.75), State of California

Department of Industrial Relations,

https://www.dir.ca.gov/dlse/RCILegReport2020.pd

f.

11

Kevin Kish, 2017 Annual Report, Department of

Fair Employment and Housing,

https://www.dfeh.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/32/2018/08/August302018

AnnualReportFinal.pdf (the 2017 annual report

refers to retaliation complaints as those concerning

“engagement in a protected activity”).

12

Kevin Kish, 2018 Annual Report, Department of Fair

Employment and Housing, https://www.dfeh.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/32/2020/01/DFEH-AnnualReport-

2018.pdf.

13

Kish, 2019 Annual Report.

14

Kish, 2018 Annual Report.

15

Kish, 2018 Annual Report.

16

Kish, 2019 Annual Report.

17

See, e.g., Advancing Justice - Asian Law Caucus and

University of California, Berkeley Labor Occupational

Health Program, Few Options, Many Risks: Low-Wage Asian

and Latinx Workers in the COVID-19 Pandemic, April 2021,

https://www.advancingjustice-

alc.org/news_and_media/covid-workers-report; Rakeen

Mabud, Amity Paye, Maya Pinto, and Sanjay Pinto,

Foundations for a Just and Inclusive Recovery: Economic

Security, Health and Safety, and Agency and Voice in the

COVID-19 Era, Color of Change, National Employment Law

Project, TIME’S UP Foundation, and The Worker Institute

at Cornell ILR, February 2021,

https://www.nelp.org/publication/foundations-for-a-just-

and-inclusive-recovery; San Diego State University

Department of Sociology, Center on Policy Initiatives, and

Employee Rights Center of San Diego, Confronting Wage

Theft: Barriers to Claiming Unpaid Wages in San Diego, July

2017,

https://ccre.sdsu.edu/_resources/docs/reports/labor/Con

fronting-Wage-Theft.pdf; Jora Trang, Improving OSH

Retaliation Remedies for Workers, Worksafe, June 2015,

https://worksafe.org/file_download/inline/54b22018-

1128-4141-842c-aebc9cdccf23; and Eileen Appelbaum and

Ruth Milkman, Leaves That Pay: Employer and Worker

Experiences with Paid Family Leave in California, 2011,

https://cepr.net/documents/publications/paid-family-

leave-1-2011.pdf.

18

CCWP Focus Groups with California members of the

Pilipino Association of Workers and Immigrants (PAWIS),

in Tagalog, held in August 2021. On file with author.

19

Institute for the Future for the California Future of Work

Commission, Future of Work in California: A New Social

Compact for Work and Workers, March 2021,

https://www.labor.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/338/2021/02/ca-future-of-work-

report.pdf.

20

“Hunger Data,” California Association of Food Banks,

https://www.cafoodbanks.org/hunger-

data/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%201%20out%20of,by

%20Black%20and%20Latinx%20families.&text=This%20

data%20is%20based%20off,not%20comparable%20to%2

0Phase%202 and Diane Schanzenbach and Natalie Tomeh,

“Visualizing Food Insecurity”, Northwestern Institute for

Policy Research, July 14, 2020,

https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/state-food-

insecurity.html (selecting for California, 23.9 percent of

Black and 24.9 percent of Latinx respondents reported

food insecurity).

21

Robert P. Jones, Daniel Cox, Rob Griffin, Maxine

Najle, Molly Fisch-Friedman, and Alex Vandermaas-

Peeler, A Renewed Struggle for the American Dream:

PRRI 2018 California Workers Survey, PRRI, 2018,

https://irvine-dot-

»

NELP | HOW CA CAN LEAD ON RETALIATION REFORMS TO DISMANTLE WORKPLACE INEQUALITY | NOV 2022

31

org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/295/attachmen

ts/2018_PRRI_California_Workers_Survey.pdf?1535

415254.

22

Catherine S. Harvey, “Unlocking the Potential of

Emergency Savings Accounts,” AAPR Public Policy

Institute, October 2019,

https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/201

9/10/unlocking-potential-emergency-savings-

accounts.doi.10.26419ppi.00084.001.pdf.

23

Harvey, 2019.

24

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S.

Households in 2018 – May 2019, last updated May 28,

2019,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019

-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2018-

dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm.

25

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, 2019.

26

Alissa Anderson, Q&A: Unemployment Insurance,

Labor Day Cliff & the Costs of Unemployment,

California Budget & Policy Center, August 2021,

https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/qa-

unemployment-insurance-labor-day-cliff-the-costs-

of-unemployment/

27

Anderson, 2021.

28

See, e.g., Lauren Hepler, “Is California blowing it

on unemployment reform?,” CalMatters, March 29,

2021, Economy,

https://calmatters.org/economy/2021/03/californi

a-unemployment-crisis-reform/; Marie Tae

McDermott and Jill Cowan, “What to Know About the

Delays in California’s Unemployment Payments,”

New York Times, January 19, 2021, California Today,

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/19/us/ca-

unemployment-payments.html; “Governor Newsom

Signs Legislation to Strengthen State Unemployment

Insurance Delivery System,” Office of Governor

Gavin Newsom, October 5, 2021,

https://www.gov.ca.gov/2021/10/05/governor-

newsom-signs-legislation-to-strengthen-state-

unemployment-insurance-delivery-system.